The Future of Museum Collections Roundtable

Summary

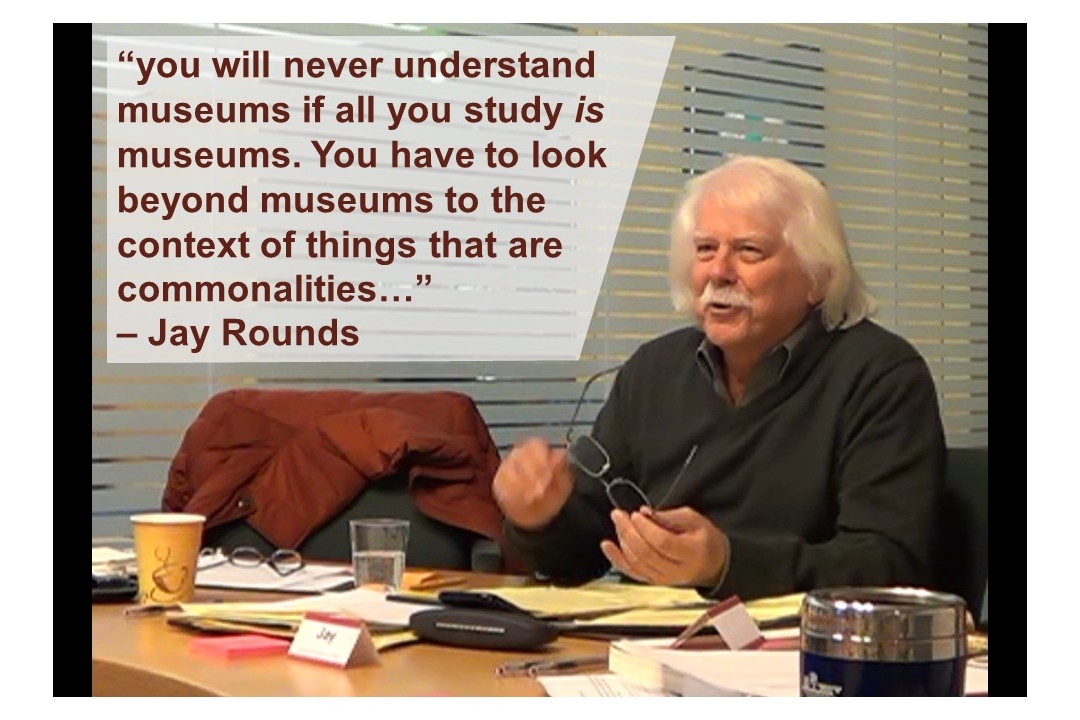

Since starting the Active Collections group in 2013, we’ve been busy gathering materials for case studies, surveying museum professional, and dreaming up ways for museums to rethink their collections. We’ve discovered a growing dissatisfaction in the field with how many museums are using (or are failing to use) their collections to advance their missions. Museums are clearly (in the worlds of Jay Rounds) in a time of “paradigm crisis” where we recognize that our old ways of doing things are no longer adequate, but we haven’t yet agreed as a field what the new systems should look like.

We feel that the “let’s collect it just in case” model that many museums use is not sustainable or justifiable and that museum collections are either a sail that helps you advance your mission, or an anchor that holds you back. To think about how to solve these issues, in November 2015, we brought together six professionals from across the country to discuss the future of museum collections and help us chart new directions for change. Funded by Indiana University’s New Frontiers in the Arts & Humanities-New Currents grant program, our roundtable participants included Jay Rounds, Benjamin Filene, Gail Steketee, Modupe Labode, Masum Momaya, and Paul Bourcier. Rainey Tisdale, Elee Wood, and Trevor Jones facilitated the discussions as well as presented their own ideas (facilitators' information can be found Here ). Graduate students Katherine Rieck, Vickie Stone, Gabriel Taylor, Amelia Whitehead, and graduate assistant Anne Jordan also participated in the roundtable discussions (all participant info can be found Here).

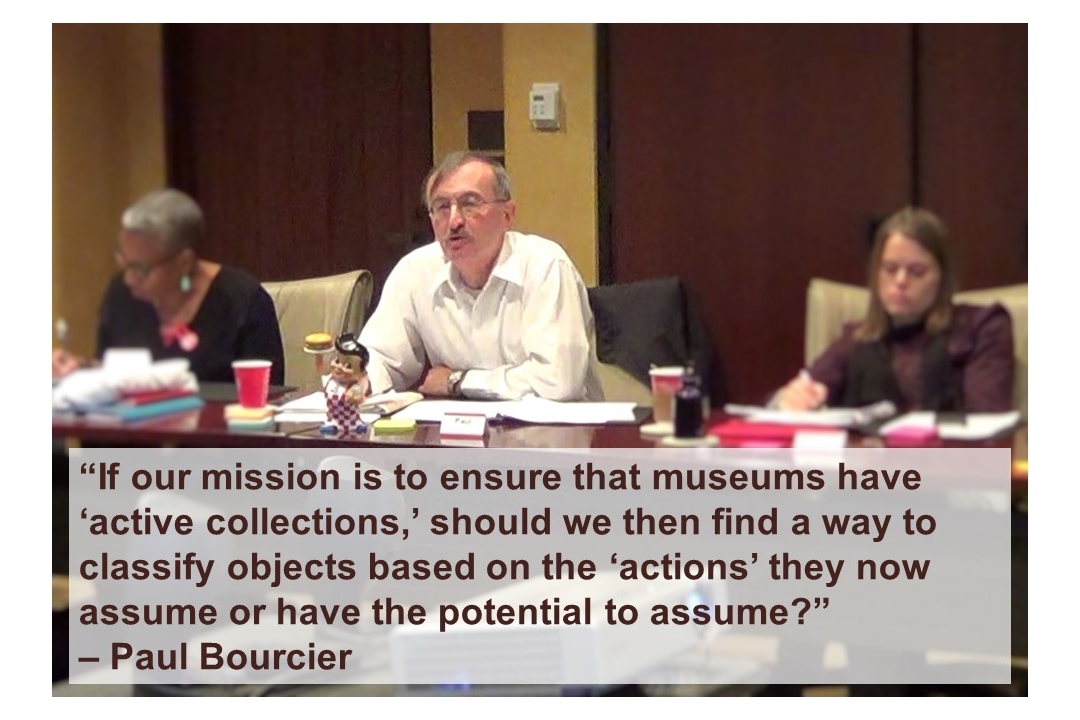

For two intense days we held a wide-ranging and productive discussion that looked at our relationship to things -- both healthy and unhealthy. Jay Rounds discussed his experience visiting a museum that bragged its collection held the world’s earliest photograph, but that no one was actually allowed to see. That prompted him to discuss the latest paradigm model we are in and how our collections fit into that. Paul Bourcier discussed the huge range of emotions objects such as a simple toy from Bob’s Big Boy can conjure up for a generation of Americans. Gail Steketee (an expert on hoarding disorders) discussed how it’s possible to get literally buried in stuff when people (and museums) can’t let go of things.

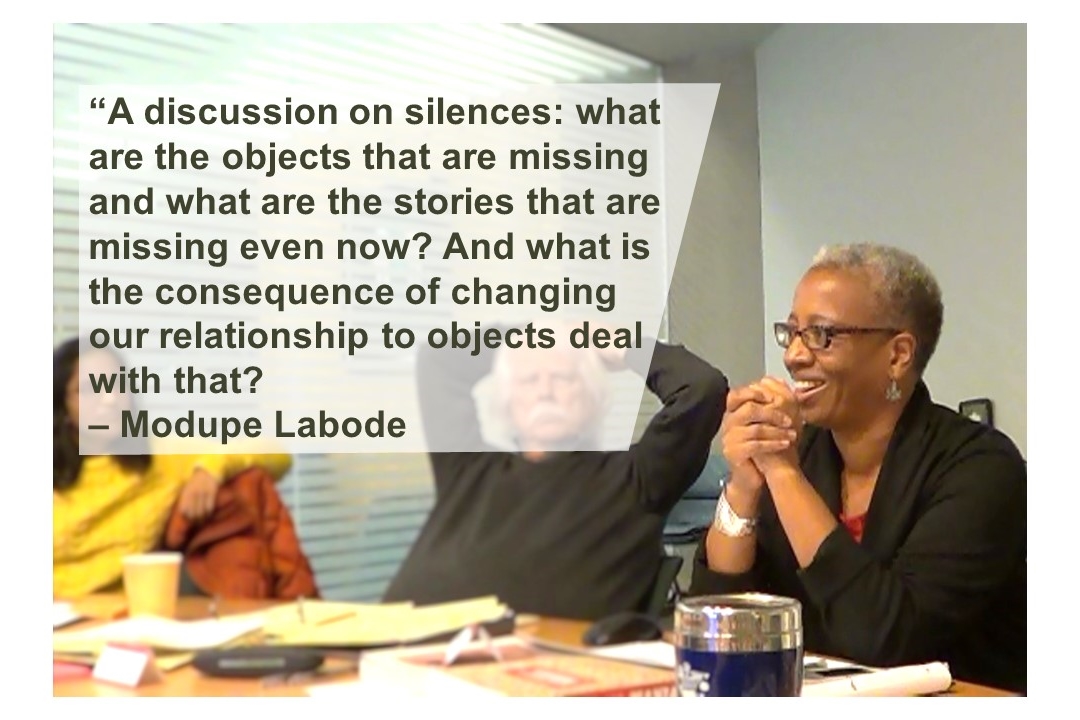

Talking about the role of collections is challenging because they are both personal and institutional. Modupe Labode talked about saving unidentified photographs of African Americans and our need to save potentially lost stories -- even if we don’t know what to do with them once they are rescued. On the institutional scale, there are great silences in museum collections where diverse voices have been left out. When we put artifacts on the shelf we catalog them in a dispassionate way and focus on their characteristics -- but not their emotion or their meaning or even what stories are not discussed. Although museum workers like to believe their catalogs are neutral, bias is inherent in the metadata. Masum Momaya talked about how trying to rectify these silences with underprivileged groups remains a challenge as it often feels like museums are trying to “legitimize” their stories and simply appropriate them in a more gentle fashion. Most museum collections are framed around the lens of privilege, and adding more diverse stories feels a lot like adding a sprinkling of more inclusive collections on top of a heap of white, elite stories.

Benjamin Filene explored the idea of time capsules in American history as an example of how what we save (and why we save it) feels eternal to us, but the truth is everything we try to preserve in a capsule is very clearly a product of our time. Why is it then that we think of museum collections as frozen in time rather than as flexible and changeable resources that can be adapted to meet our changing needs? Part of our challenge is that many museums feel they are not collecting for the people of today, but rather for the future. When that’s the argument, trying to imagine what future researchers may or may not want gets very difficult to predict. The idea that museum curators have some sort of innate ability to make objective decisions about what’s important for all eternity troubles us deeply.

The result is that we collect lots of things that will never get used, which drains our resources and is unsustainable for most institutions. While our discussions did not lead to any immediate solutions, we did come up with many ideas and desires we wish for museums to look into for the future. These suggestions and other research questions can be found under the Research Agenda.

Highlights

Look for summaries of each participant in the coming weeks to learn more about their contributions to our converstaions. In the mean time, watch the video provided below to hear some anecdotal stories and highlights from four of our participants.

*Note* The title of Modupe Labode's highlight is a reference to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's TED talk entitled "The Danger of a Single Story."