Jay Rounds Summary

Summary written by graduate assistant Anne Jordan

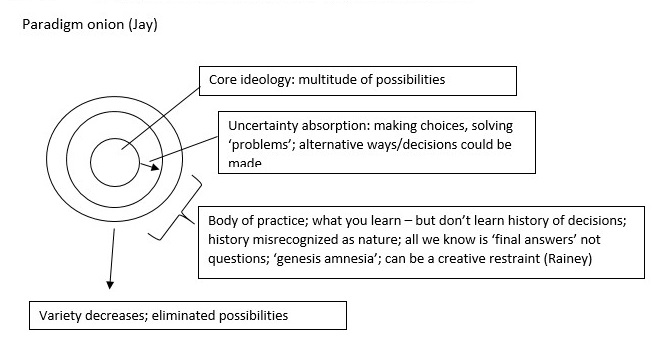

Dr. Jay Rounds was a Roundtable participant who had a lot of information to add to the conversation. One of his more interesting points, and the topic of his speech, was this idea of paradigm shifts in museums. Paradigm, as he explains, are systems that start with a core idea- a problem that needs to be solved. It is then surrounded by solutions that build on top of each other, creating a circle with rings surrounding it-similar to an onion. As more solutions get added to the core problem, society begins to forget what the starting point even was and the number of new ideas is decreases while solutions become more about efficiency. It is at these times when we see periods of stability and a lack of idea diversity in museums. However, at some point people begin to question the whole system and that is when we find ourselves in a paradigm shift or crisis.

Museums are currently in a paradigm crisis, but this is not the first time. As Dr. Rounds explains, crises have taken place in museums throughout history and these changes of ideas lined up with paradigm shifts in other institutions, namely prisons and schools. In fact, there have been three major paradigm shifts in history; in the 1800's, the 1900's, and the one we see today.

The first paradigm shift happened in the wake of the Revolutionary War when the country was fearful of the future. Society drew from the Enlightenment which highlighted the idea that we could have liberty and tyranny simultaneously to ensure our ideas of freedom were consistent. The penitentiary system was built around the idea that everyone had a rational mind and crime was a social problem. Criminals weighed costs and benefits of committing crimes so if punishments were extreme enough, crime would seize. Similarly, education systems were dominated by Classics and the idea that the mind is a muscle that needs to be exercised. Museums then, were constructed around the idea that they were institutions meant to inspire the individual to study themselves. Everything seen in the cases were an extension of what God created, so one of everything had to be displayed.

100 years later, evolutionary theory was on the rise. With that came the concept that being human meant internalizing culture, so teachers in school were the ones in control. They had an obligation to extend their knowledge to the uninformed, thereby “evolving” them. Prisons followed a similar path and believed criminals could change and evolve, thus emphasizing reform over punishment. Collections in museums showed artifacts in a sequence that led to the present form of everything, again exemplifying evolution.

Now we find ourselves in another shift, this time focusing on multicultures and diverse approaches to everything. There is no longer just one way of teaching or one correct story to tell; we believe in the idea of the individual mind instead of group mentalities. Schools are looking into new ways of teaching, focusing on students’ specific needs and desires. In museums, we display objects as a reminder of the reality of culture and the individual’s participation in it. We acknowledge people do not internalize culture as much as we previously thought and social order comes out of our differences, not sameness.

So what does all of this mean? It means we are starting to discuss new theories and reexamine our experts in the field. We no longer believe that curators hold all the answer and instead look to the visitors for information, context, and confirmation. When will the “crisis” be over? It’s difficult to say. As Dr. Rounds points out, the key to changing our current paradigm is destroying the old one completely. Professionals are slow to change, but with new research and emerging professionals, we will hopefully return to a period of stability soon.

Diagram created by Vickie Stone